On the road to Tarascon and beyond.....

Vincent Van Gogh, The Painter on his way to work / The Road to Tarascon 1888, oil on canvas. Now lost or destroyed.

Australian artist Martin Sharp (1942-2013) was fascinated by Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890). Beginning with his childhood, he read about the Dutch artist's life and work, trawled through his many published letters, and incorporated van Gogh's imagery and motifs within his own work, whether it be drawing, collage, graphic design, posters or painting. Sharp was also keen to highlight the significance of the artist to others. He perhaps saw in van Gogh's tragic life and extraordinary output over a relatively short period of time a reflection of his own less-tragic journey and experiences in art. This article will attempt to chart the course of Sharp's developing interest in, and fascination with, Vincent van Gogh, as revealed primarily through his published, printed and painted works from the late 1960s through to the 2000s.

Paul Gauguin, Emile Bernard, Vincent van Gogh (smoking a pipe), André Antoine (standing), Félix Jobbé-Duval and photographer Jules Antoine, Paris, 96 rue Blanche, December 1887. Photograph discovered in 2015 and supposedly the only one known of van Gogh during his later life as an artist.

Martin

Sharp was born in Sydney in 1942. His father was a dermatologist and in

his North Shore surgery there hung a framed print of Vincent Van Gogh's The Painter on his way to work / The Road to Tarascon 1888.

Sharp saw it often as a child, and it struck a chord with the young

and talented artist. He treasured the print throughout his life, eventually hanging it in a prominent position in his Sydney house,

Wirian, where it remained until his death in 2013. It was a link not only to his

father and childhood, but also to an artist who would become an

major inspiration as Sharp moved into adulthood and on to a role as a

professional artist. Whether he knew it or not, by the time he first noticed the print, the original artwork no longer existed. Where it once hung in the Kaiser

Friedrich Museum in Magdeburg, Germany, it had been

destroyed by fire, either during 1933 or in World War II. It is now only known through

photographs. The original painting was a simple work in content and composition, portraying the artist walking to or from his work at painting out of doors, in the fields near the road between Arles and Tarascon, France. The relatively simple, faceless figure of van Gogh, with his distinctive hat, paint palette in one hand, folio in another and pack with easel on his back, looks out towards the viewer, whilst on the ground his black, ghostly shadow trails along the golden pebbled road. The painting intrigued Sharp, and his interest in von Gogh was enhanced when the art master at Cranbrook High School, Justin O'Brien, awarded him a prize one year consisting of a book on the artist. Sharp no doubt devoured its content at the time and put the stories and imagery away in his memory for later consideration and application. For a later prize, Sharp requested a copy of the van Gogh biography Lust for Life (Stone 1934) which formed the basis for the 1956 Hollywood film featuring Kirk Douglas. Later in life Sharp reflected on his early relationship with van Gogh:

He was the first artist I became interested in because his drawing style was very simple. It was part of his plan that the intended to reach as many people as he could and he certainly reached me when I was a boy. The first painting I ever copied was a Van Gogh still life, on Justin O'Brien's suggestion. I got an art prize at school, a book of his life, and I was interested to see the film Lust for Life. He knew when he started painting he'd have ten years to live if he kept up that same work pace - he was exactly accurate of course. (Slutzkin & Haynes 1979)

Sharp's Still Life (after van Gogh) 1956 was the painting he was referring to, based on a original painting by the artist featured in a William Heinmann 1954 publication which was his art prize. Vincent van Gogh was not initially a major reference point within the art of Martin Sharp. His paintings, cartoons and work with Sydney OZ magazine and local newspapers and student magazines between 1962 and the beginning of 1966, when he left Sydney for on an overland journey to London, does not contain any obvious references to the Dutch painter. This changed following his arrival in Britain around August of 1966. From then through until the end of 1968 Sharp experienced all that London had to offer during the so-called Swinging Sixties and Summer of Love - the sex, drugs and rock and roll were laid out before the young Australian artist, along with access to the heritage of European art via the many galleries and museums, both in Britain and on the Continent. Sharp used his time there, and his abiding interest in the history of art, to educate himself in regards to those artists and movements that interested him. His knowledge of Dada and Surrealism evolved, and an early fascination with German Expressionism extended to new areas of interest such as Japanese woodblock prints and French Impressionism, but more specifically the art of Vincent van Gogh. At last he was able to see original works by the artist and had ready access to the many publications containing reproductions of the more famous pieces, especially van Gogh's later works in oil.

He was the first artist I became interested in because his drawing style was very simple. It was part of his plan that the intended to reach as many people as he could and he certainly reached me when I was a boy. The first painting I ever copied was a Van Gogh still life, on Justin O'Brien's suggestion. I got an art prize at school, a book of his life, and I was interested to see the film Lust for Life. He knew when he started painting he'd have ten years to live if he kept up that same work pace - he was exactly accurate of course. (Slutzkin & Haynes 1979)

Sharp's Still Life (after van Gogh) 1956 was the painting he was referring to, based on a original painting by the artist featured in a William Heinmann 1954 publication which was his art prize. Vincent van Gogh was not initially a major reference point within the art of Martin Sharp. His paintings, cartoons and work with Sydney OZ magazine and local newspapers and student magazines between 1962 and the beginning of 1966, when he left Sydney for on an overland journey to London, does not contain any obvious references to the Dutch painter. This changed following his arrival in Britain around August of 1966. From then through until the end of 1968 Sharp experienced all that London had to offer during the so-called Swinging Sixties and Summer of Love - the sex, drugs and rock and roll were laid out before the young Australian artist, along with access to the heritage of European art via the many galleries and museums, both in Britain and on the Continent. Sharp used his time there, and his abiding interest in the history of art, to educate himself in regards to those artists and movements that interested him. His knowledge of Dada and Surrealism evolved, and an early fascination with German Expressionism extended to new areas of interest such as Japanese woodblock prints and French Impressionism, but more specifically the art of Vincent van Gogh. At last he was able to see original works by the artist and had ready access to the many publications containing reproductions of the more famous pieces, especially van Gogh's later works in oil.

Martin Sharp, Vincent, Big O Posters, London, April 1968.

1968

Sharp's first public manifestation of an interest in the life and art of van Gogh was the Vincent poster published by Big O Posters in A 1968. This collage melding of the psychedelic with the reproduction of no less than nine van Gogh self portraits, suitably transformed by surrealistic touches, was a glorious explosion of colour using a basic yellow palette. It was nothing less than a homage to Vincent van Gogh, pointing to the Sharp's revelatory linking between his experiences in London over the previous two years, and the way forward as indicated by his study of the Dutch painter. The poster was both a signpost and a portrait of where Sharp was at. The acid bubbles and wavy lines, the intense colour and the complex phantasmagoria of imagery was pure LSD - a trip transferred to paper. The many visions Sharp saw of the face of Vincent van Gogh spilled out onto the Big O poster in a frenetic display of artistry. In amongst its collage and painterly elements, the poster highlighted a quote from a van Gogh letter which obviously resonated with Sharp, namely: "I have a terrible lucidity at moments when nature is so glorious in those days I am hardly conscious of myself and the picture comes to me like in a dream..." These words go to the core of van Gogh's art, in that, as revealed by his letters to his brother Theo, he put a lot of thought into his work and the development of his drawing and painting, such that, towards the end of his life it became an almost unconscious act, as in a dream. The use of psychedelic drugs such as LSD by Sharp during late 1966 and into 1967 undoubtedly expanded his own consciousness and opened him up to the possibilities of the dream, as is seen in his suite of psychedelic posters produced for Big O around the themes of personal heroes including Bob Dylan, Donovan, Michelangelo and van Gogh. The Vincent poster from 1968 was one of the last one of these, and the aforementioned quote perhaps reflects the fact that Sharp had developed his art to that same level whereby it was almost an expression of his subconscious. Whatever the case, during early 1968 he found something in the art and writing of van Gogh which offered him a path on his own journey. And so he began to feature the great artist in his work, as one of the many motifs which he would repeatedly use and adapt throughout his lifetime. Van Gogh, Mickey Mouse and Ginger Meggs would be some of the recurring characters in the maze of imagery Sharp presented to the world at large over the next 45 years. The Vincent poster appears to have been the start of that. It was initially promoted in a Big O Posters advertisement in OZ magazine number 11 of April 1968, and within an article in the following issue, though then only as a small black and white reproduction. Van Gogh next appeared in OZ magazine number 16 of November 1968. This was the issue edited by Sharp and consisting entirely of collage. Van Gogh featured on three pages within the 64 page edition, which Sharp titled The Magic Theatre, after the Herman Hesse novel Steppenwolf.

Martin Sharp, The Road to Tarascon, OZ magazine number 16, London, November 1968.

This small cartoon-like strip represents Sharp's first publish adaptation of the character of the travelling artist, as seen in The Road to Tarascon. In it Sharp has his figure walking in the opposite direction to the original, and therein replicated four times, with the final figure on the right a mere outline in both reality and shadow. The second van Gogh item in The Magic Theatre is a cutout of a self portrait of the artist, juxtaposed next to a still from the 1933 movie King Kong which in turn is superimposed over a background crowd scene. Sharp has annotated the van Gogh portrait with the words: Perhaps the finest self portrait .... of death.

Martin Sharp, Perhaps the finest self portrait .... of death, OZ magazine number 16, London, November 1968.

The third and final item is a full page in colour featuring two works by Sharp - the first an outline based on one of van Gogh's self portraits and with the inscription: Life is probably round. Vincent. Below that is a reproduction of van Gogh's Airing of the Asylum Residents 1890. In between the two are two Maybridge walking figures - motifs Sharp made use of in numerous works during 1968.

Martin Sharp, Life is probably round. Vincent, OZ magazine number 16, London, November 1968.

Sharp's version of one of van Gogh's last works, dating from his period in the asylum, varies from the original in regards to the enhancement of the artist's figure. Sharp makes van Gogh stand out by giving him a dark blue outfit and a bright yellow sparkling halo. In the original he is seen with very short, blond hair, walking erect as those around him slump in their tracks. Not long after this work was complete, van Gogh committed suicide.

Vincent van Gogh, Airing of asylum residents, 1890.

Also around 1968 Sharp began experimenting with painting and drawing on mylar / plastic. One of the first successful works in this regards was the combination of van Gogh's Self-portrait with pipe and Chair.

1969

* hippie Mickey, 'n Vince

Sharp left London at the end of 1968 and returned to his home town of Sydney. He remained there for only a relatively brief period of time before heading back to London where he spent the second half of 1969. During that visit he continued to develop his interest in van Gogh and discussed with his artist and filmmaker friend Albie Thoms a plan to set up an artists community in Sydney similar to van Gogh's own ill-fated Yellow House venture in Arles. Whilst back in Britain in 1969 Sharp also produced a poster for Big O known as Vince n' Mickey / Fancy our meeting. It featured a cartoon version of the artist on the road to Tarascon, accompanied by Mickey Mouse, with a blank text bubble between them.

Sharp explained how the work came together in an interview for a 1979 travelling exhibition by the Art Gallery of New South Wales. He noted in the exhibition catalogue:

I had done an abstraction of Vincent on the Road ... with a thought line going up to heaven. I had that against the wall and a cutout figure of Mickey Mouse which I was working on. They were lying against each other and I thought 'That looks good' - I put a piece of perspex over the two of them and tracing it over and that was the picture. Quite a breakthrough picture for me I think - that's when I did bring the two worlds together. It was done as a painting and turned into a poster - it's nice to see them up on the streets. (Slutzkin & Haynes 1979).

Sharp left London at the end of 1968 and returned to his home town of Sydney. He remained there for only a relatively brief period of time before heading back to London where he spent the second half of 1969. During that visit he continued to develop his interest in van Gogh and discussed with his artist and filmmaker friend Albie Thoms a plan to set up an artists community in Sydney similar to van Gogh's own ill-fated Yellow House venture in Arles. Whilst back in Britain in 1969 Sharp also produced a poster for Big O known as Vince n' Mickey / Fancy our meeting. It featured a cartoon version of the artist on the road to Tarascon, accompanied by Mickey Mouse, with a blank text bubble between them.

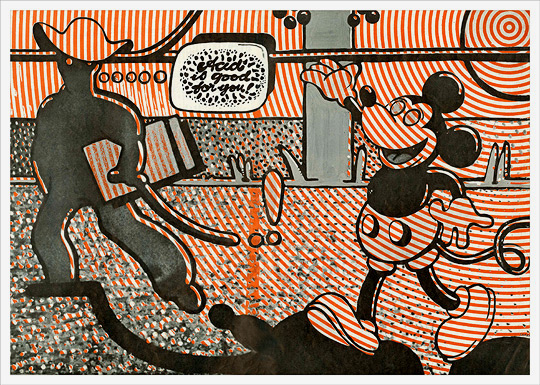

Martin Sharp, Vince n' Mickey / Fancy our meeting, Big O Posters, London, 1969/70.

Sharp explained how the work came together in an interview for a 1979 travelling exhibition by the Art Gallery of New South Wales. He noted in the exhibition catalogue:

I had done an abstraction of Vincent on the Road ... with a thought line going up to heaven. I had that against the wall and a cutout figure of Mickey Mouse which I was working on. They were lying against each other and I thought 'That looks good' - I put a piece of perspex over the two of them and tracing it over and that was the picture. Quite a breakthrough picture for me I think - that's when I did bring the two worlds together. It was done as a painting and turned into a poster - it's nice to see them up on the streets. (Slutzkin & Haynes 1979).

The image was to be reused on a number of occasions, by Sharp and others. The first controversial reuse was within the May 1970 edition of London OZ magazine as a two-page spread with the words "Acid is good for you!" added by one of the editors, Jim Anderson, along with orange, psychedelic circles. Sharp had by this time returned to Australia and was upset with this unauthorised adaptation of his work. By this time he was no longing using LSD / Acid and did not want to promote its use. Marijuana and tobacco were his new drugs of choice.

* 'artoon Art

Sharp subsequently reworked this subject, revealing the Andy Warhol image in dayglo colours. A version appeared in Sharp's Art Book during 1972 (refer above). The 1973 version in the Australian National Gallery collection was done in Australia with the assistance of artist Tim Lewis. The vibrant use of acrylic paints on a large canvas produced a stunning work which expresses the innovation and artistry of Martin Sharp.

* Margaret Jones, Whatever happened to Martin Sharp?, Sydney Morning Herald, 16 May 1970.

"The images have been imprisoned inside me for too long: they want to get out," says Martin Sharp, clattering through the old Clune galleries in Macleay Street, in heavy-blue clogs, long bob swinging on denimed shoulders. The images appear in lithographs stacked against the walls, in silk screen on plastic, in works.in-progress stretched out on the floor for want of other space. Sharp is not yet ready for the opening of his show of paintings, collages, lithographs and posters next Wednesday. "Life is a whirlpool draining towards a small hole," he says, with an air of gentle perturbation. Whatever happened to the old Martin Sharp, with his savage comic-strip fables, his elaborate collages, his inspiring attacks on Establishment figures, who often immortalised their own inanities in the balloons issuing forth from their mouths? Whatever happened to the terrible triplet, who, with Richard Neville and Richard Walsh, published the highly satirical magazine "Oz"? The old Sharp still exists, manifesting in the posters and collages, particularly some of the vintage works. The posters are a special joy, richly ornamental as well as significant, ravishing in gold and silver. But, on the whole, these days the images are simple, profound, and quintessential: hearts, flying objects, flowers with human lips for blossoms, an unadorned question mark. Space gets a passing glance, as in a portrait of an astronaut against a galactic background. Pop is present, naturally, both in style and in matter with a self portrait that looks like John Lennon ("the superficial characteristics are the same," says Sharp) and a painting of Mick Jagger, which is also growing to look like its creator.

What you might call a van Gogh theme is becoming increasingly predominant. "The more I know of him, the more I come to feel he was a saint," Sharp says. A large portrait of Saint Vincent will be the outstanding motif of the show. Vincent appears again in the posters, with a balloon quote: "I have a terrible lucidity at moments, when nature is so glorious. In these days I am hardly conscious of myself and the picture comes to me like a dream."

Martin Sharp. scion of respectable Belleview Hill, once notorious as the author of "The Gas Lash," is a more familiar figure nowadays in the psychedelic world of the London Underground - the latter-day Bohemia - than in his native Sydney. He is back for this show, for some sunshine, and to refresh himself in the waters of beautiful Bondi. (No irony seems intended. "It" really hypnotises me," he says. "Nature in the heart of the city.'') One thinks of Sharp, Neville and Walsh as Perpetually terrible children. Martin Sharp is, in fact, a tall, slim man of 28 (almost middle aged as things go nowadays) with a heavy fall of dark hair half-hiding his face. He has made a considerable name for himself in London as a poster-designer, and has been working with Richard Neville on the London "OZ." When I was in Britain, "OZ" was, with malice aforethought, printed in type so small that no one over 30 could read it. This may soon invalidate Martin, even if be does not already feel that he and "OZ" are drifting apart. It is now, he says, revolutionary only in a large-circulation magazine sort of way. At the moment, he is experimenting in the op and pop art field, painting on clear plastic from in front and behind, in acrylic paints and enamels. It is still comment on the social scene but much less cruelly ironic than in the days when he bit the hand that fed him.

"When I lived in Sydney, I was trying to preserve my own integrity, building a wall around myself so I could exist in the middle," he says. "In London, I don't feel the necessity for this." It was a shock to come back after four years though, to find "Tharunka" being prosecuted again under the Obscene and Indecent Publications Act: pure deja vu. 1t was, after all, Sharp's prosecution and sentencing over the publication of "The Gas Lash" in Tharunka" which brought him local notoriety. Sharp's views on censorship haven't changed much: He sees the publication of the ballad "Eskimo Nell" as the action of waving a red rag at a lumbering bull, a rag which the easily stimulated bull obediently charges. Sharp has also some not-quite formulated ideas about the function of censorship in hot and cold climates. Permissiveness is allowed more easily, he thinks, in cooler climes, where the level of physical sensuality is lower, and the inhabitants are presumably less likely to be emotionally aroused. (This doesn't account for Russia or Ireland of course, but the idea is interesting.) Some o f Australia's censorship troubles, he feels, are accounted for by the dilemma of an Anglo Saxon culture being translated into a Mediterranean climate, and so becoming disoriented. Australia, excited and open, and being confronted with the cold barriers thrown up by the Customs men, was also a blow. "I had some colour slides of nudes, and they took them away and screened them," he says. "They asked if I had any pornographic literature, so I offered them a copy of 'Playboy' to placate them. It didn't work. They went through the letters of van Gogh and Patrick White's "'Tree of Man' to see if there were any dirty words in them.'' Sharp does not share the view first put forward by D. H. Lawrence, and echoed regularly ever since, that Australians are a mindless lot, obsessed solely with sensual pleasures. In the 1920s, Lawrence found no evidence that culture was alive and well and living in Sydney. "The absence of any inner meaning; and, at the same time, the great sense of a do-as-you-please liberty. And all utterly uninteresting ..... Great swarming teaming Sydney flowing out into those myriads of bungalows, like shallow water spreading undyked. And what then? Nothing. No inner life, no high command, no interest in anything, finally." But Sharp, fresh from pulsating London, finds the local scene very exciting, though he can't as yet define why. Things are happening here which are not recognised. The form is imitative, but not the content. 'That is why Australians are so successful in the London Underground," he says. "You will find that most Underground activities are run by Americans and Australians. It is the ideas which are different." Martin Sharp is the precursor of a group of expatriate Australians who will descend on us from the skies by charter plane in the coming spring. About 150 are talking of making the trip: writers, artists, film makers, rock stars, hippies, a planeload of cultural gurus, or, if you like. guerillas. It is a sort of colonial echo, Martin Sharp says. The British used to send us seminal people to stimulate our culture. Now our emissaries, carried abroad by the cultural brain drain, will return for a process of cross-fertilisation.

Martin Sharp & Jim Anderson, Vince n' Mickey, OZ Magazine, London, May 1970.

The actual Big O poster appeared on the cover of the company catalogue during 1971, beneath a title 'It Must Be Art'.

Sharp would also receive some redress and satisfaction from the OZ editors when his updated Eternity version later appeared in one of the final editions of London OZ during 1973. This time around no colour was added and the only inscription was by the artist - the word Eternity in large letters across the top of the image, and a question mark in the text bubble.

* Van the boxer

Sharp would also receive some redress and satisfaction from the OZ editors when his updated Eternity version later appeared in one of the final editions of London OZ during 1973. This time around no colour was added and the only inscription was by the artist - the word Eternity in large letters across the top of the image, and a question mark in the text bubble.

Martin Sharp, Eternity / Vince n' Mickey, OZ magazine number 46, January 1973.

* Van the boxer

Another work which originated from Sharp's 1969 visit

to London was the portrait of a boxing van Gogh. It initially appeared

as a Big O poster published around 1969-70. That version was in mute

brown and purple colours. It is unclear exactly what brought Sharp to paint van Gogh in the role of a boxer.

A more colourful version was subsequently got up during 1970 using acrylic paint on mylar. It is marked by a bright blue speckled background rimmed with vivid red. The boxing artist used distinctive yellow gloves.

Martin Sharp, Van Box, poster. Big O Posters, London, circa 1969. Advertisement from OZ magazine.

|

| Martin Sharp, Van Box, poster. Big O Posters, London, circa 1969. |

A more colourful version was subsequently got up during 1970 using acrylic paint on mylar. It is marked by a bright blue speckled background rimmed with vivid red. The boxing artist used distinctive yellow gloves.

Martin Sharp in the Yellow House, Sydney, 1971. Boxing Van Gogh in the background.

* 'artoon Art

Perhaps the most significant development during 1969 was Sharp's exhibition of his expanding collection of 'artoons, which were collages of images from well-known paintings, cut from books. They were first revealed to the public during the exhibition 'Artoons by Sharp Martin and his Silver Scissors, held at the Sigi Krauss Gallery, London, between 6 March and 18 April 1969. The works were presented in mirrored frames with mitred corners. An advertisement for the exhibition features an adaptation of van Gogh's chair.

In association with a later exhibition held in London between 19-21 November 1972, Sharp issued a small book containing copies of 38 of the 'artoons. Titled simply Art Book, van Gogh featured in thirteen of the published works. As Robert Lindsay noted in his introductory essay to Sharp's 1981 exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria:

In Martin Sharp's art there is a family of popular heroes and he as artist, acts as host introducing old friends to new, helping to form and create happy alliances between images of the past and present. Thus in his 'artoons Picasso meets Conder, Lichtenstein meets Mondrian, Goya meets Whistler, and van Gogh as the guest of honor, is toasted by all. (Lindsay 1981).

The works reproduced in Art Book have variously originated from his initial forays into 'artoons in 1968/9 and Sharp's subsequent development of the form through to 1972. The thirteen Art Book works featuring van Gogh are reproduced below:

Plate 2: Martin Sharp / Van Gogh Self portrait 1889

Plate 3: Georgio De Chirico Piazza d'Italia con Monumento di Uomo Politico 1965 / Van Gogh Starry Night 1889

Plate 4: Rene Margitte The Explanation 1954 / Van Gogh Night Cafe 1888

Plate 5: Van Gogh The Road to Trarascon

Plate 6: Van Gogh Sunflowers / Pierre Bonnard Nude before a Mirror 1934

Plate 7: Paul Cezanne Vessels, Basket and Fruit, The Kitchen Table 1888-90 / Van Gogh The Road to Tarascon

Plate 8: Andy Warhol Marilyn 1962 / Van Gogh Sunflowers 1888

Plate 9: Edgar Degas The Star 1878 / Van Gogh The Sower 1888

Plate 10: Rene Magritte The Golden Legend 1958 / Van Gogh Langlois Bridge at Arles 1888

Plate 26: Edvard Munch Puberty 1895 / Van Gogh The Night Cafe 1888

Plate 27: Van Gogh Self Portrait / Francis Bacon Portrait of George Dyer Talking 1966

Plate 35: Roy Lichtenstein Yellow and Green Brushstrokes 1966 / Van Gogh Chair with Pipe 1888

Additional 'artoons were produced by Sharp which did not appear in Art Book. Some were also later converted to pen and ink drawings and full size painting. Those 'artoons featuring van Gogh works include the following (reproduced from black and white copies):

[IMAGE ]

Sharp's time in London during 1969 also gave rise to the first version of what was to become one of his most famous works. Known as Still Life, it began life as a collage featuring a photographic portrait by Andy Warhol of Hollywood actress and tragic sex goddess Marilyn Monroe, superimposed upon van Gogh's most famous work - Sunflowers, from one of the series painted at the Yellow House in Arles, France, during 1888. Sharp's work appeared on the rear cover of OZ magazine number 26 during February 1970. It was printed in two colours similar to the cover - a metallic greenish grey base with the image in a monotone red. It also advertised, faintly in the top right corner, the exhibition SMART 'ARTOONS by Sharp Martin and his Silver Scissors at the Sigi Kruass Gallery from March 1st for four weeks, 29 Neal St. Covent Garden, 836-2662.

Martin Sharp, SMART! - 'Artoons by Sharp Martin and his Silver Scirrors!!!! Til April 18th at the Sigi Kruass Gallery, 29 Neal St. Covent Garden [1969]. Pen and ink advertisement. Reproduced in Underground Graphics (1970).

In association with a later exhibition held in London between 19-21 November 1972, Sharp issued a small book containing copies of 38 of the 'artoons. Titled simply Art Book, van Gogh featured in thirteen of the published works. As Robert Lindsay noted in his introductory essay to Sharp's 1981 exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria:

In Martin Sharp's art there is a family of popular heroes and he as artist, acts as host introducing old friends to new, helping to form and create happy alliances between images of the past and present. Thus in his 'artoons Picasso meets Conder, Lichtenstein meets Mondrian, Goya meets Whistler, and van Gogh as the guest of honor, is toasted by all. (Lindsay 1981).

The works reproduced in Art Book have variously originated from his initial forays into 'artoons in 1968/9 and Sharp's subsequent development of the form through to 1972. The thirteen Art Book works featuring van Gogh are reproduced below:

Cover: Van Gogh Wheatfield with Cypresses 1889 / Magritte Philosophy in the Boudoir 1947

Plate 2: Martin Sharp / Van Gogh Self portrait 1889

Plate 3: Georgio De Chirico Piazza d'Italia con Monumento di Uomo Politico 1965 / Van Gogh Starry Night 1889

Plate 4: Rene Margitte The Explanation 1954 / Van Gogh Night Cafe 1888

Plate 5: Van Gogh The Road to Trarascon

Plate 6: Van Gogh Sunflowers / Pierre Bonnard Nude before a Mirror 1934

Plate 7: Paul Cezanne Vessels, Basket and Fruit, The Kitchen Table 1888-90 / Van Gogh The Road to Tarascon

Plate 8: Andy Warhol Marilyn 1962 / Van Gogh Sunflowers 1888

Plate 9: Edgar Degas The Star 1878 / Van Gogh The Sower 1888

Plate 10: Rene Magritte The Golden Legend 1958 / Van Gogh Langlois Bridge at Arles 1888

Plate 26: Edvard Munch Puberty 1895 / Van Gogh The Night Cafe 1888

Plate 27: Van Gogh Self Portrait / Francis Bacon Portrait of George Dyer Talking 1966

Plate 35: Roy Lichtenstein Yellow and Green Brushstrokes 1966 / Van Gogh Chair with Pipe 1888

Additional 'artoons were produced by Sharp which did not appear in Art Book. Some were also later converted to pen and ink drawings and full size painting. Those 'artoons featuring van Gogh works include the following (reproduced from black and white copies):

Martin Sharp, Van Gogh's last painting with Gauguin Dish (Tahitian Woman with Mango Blossoms), collage.

[IMAGE ]

Baconian Billiards

Martin Sharp, Footloose Magritte in Van Gogh Territory, pen and ink.

Sharp's time in London during 1969 also gave rise to the first version of what was to become one of his most famous works. Known as Still Life, it began life as a collage featuring a photographic portrait by Andy Warhol of Hollywood actress and tragic sex goddess Marilyn Monroe, superimposed upon van Gogh's most famous work - Sunflowers, from one of the series painted at the Yellow House in Arles, France, during 1888. Sharp's work appeared on the rear cover of OZ magazine number 26 during February 1970. It was printed in two colours similar to the cover - a metallic greenish grey base with the image in a monotone red. It also advertised, faintly in the top right corner, the exhibition SMART 'ARTOONS by Sharp Martin and his Silver Scissors at the Sigi Kruass Gallery from March 1st for four weeks, 29 Neal St. Covent Garden, 836-2662.

-------------------------

1970

* Marilyn's still life & sunflowers

Martin Sharp, Marilyn Sunflowers, OZ magazine number 26, February 1970. Rear cover.

Sharp subsequently reworked this subject, revealing the Andy Warhol image in dayglo colours. A version appeared in Sharp's Art Book during 1972 (refer above). The 1973 version in the Australian National Gallery collection was done in Australia with the assistance of artist Tim Lewis. The vibrant use of acrylic paints on a large canvas produced a stunning work which expresses the innovation and artistry of Martin Sharp.

|

| Martin Sharp and Tim Lewis, Still Life 1973. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas. Collection: National Gallery of Australia. |

Martin Sharp, Still Life 1990-99. Acrylic on canvas. Private Collection.

* The chair

Apart from the nine portraits of van Gogh which Sharp had featured in his

1968 poster, other works by the artist were also favoured, such as The

Chair and the Billiard Room. The former was to feature in a number of

works, one of which from 1970 is simply titled My only inspiration is imagination 1970.

Martin Sharp, My only inspiration is imagination / Vincent's chair in the Starry Night 1969. Silkscreen print on perspex.

This is an interesting work as it united Sharp's famous

black and white penmanship - in this instance in the form of a

pyschadelic background - with a simply coloured version of van Gogh's

chair. The artwork was done on a perspex sheet, such that from the other side the view is reversed, and the chair is reversed as opposed to the original work by van Gogh. In regards to that, Sharp noted:

The chair, he gave so much power to it - no one's ever just painted a chair before - he was bringing surrealism into it, making it a supernatural chair. (Slutzkin & Haynes 1979).

Another work combined van Gogh with Magritte, whilst in 1973 Sharp produced a detailed pen and ink version of the van Gogh self portrait with pipe and chair.

The chair, he gave so much power to it - no one's ever just painted a chair before - he was bringing surrealism into it, making it a supernatural chair. (Slutzkin & Haynes 1979).

Another work combined van Gogh with Magritte, whilst in 1973 Sharp produced a detailed pen and ink version of the van Gogh self portrait with pipe and chair.

Martin Sharp, Vincent's chair in Magritte's imagination, 1971, collage.

Martin Sharp, Vincent's chair, 1973, pen and ink.

Whatever happened to Martin Sharp?

Margaret Jones discovers that the terrible triplet of 'OZ' days has turned to simple images.

"The images have been imprisoned inside me for too long: they want to get out," says Martin Sharp, clattering through the old Clune galleries in Macleay Street, in heavy-blue clogs, long bob swinging on denimed shoulders. The images appear in lithographs stacked against the walls, in silk screen on plastic, in works.in-progress stretched out on the floor for want of other space. Sharp is not yet ready for the opening of his show of paintings, collages, lithographs and posters next Wednesday. "Life is a whirlpool draining towards a small hole," he says, with an air of gentle perturbation. Whatever happened to the old Martin Sharp, with his savage comic-strip fables, his elaborate collages, his inspiring attacks on Establishment figures, who often immortalised their own inanities in the balloons issuing forth from their mouths? Whatever happened to the terrible triplet, who, with Richard Neville and Richard Walsh, published the highly satirical magazine "Oz"? The old Sharp still exists, manifesting in the posters and collages, particularly some of the vintage works. The posters are a special joy, richly ornamental as well as significant, ravishing in gold and silver. But, on the whole, these days the images are simple, profound, and quintessential: hearts, flying objects, flowers with human lips for blossoms, an unadorned question mark. Space gets a passing glance, as in a portrait of an astronaut against a galactic background. Pop is present, naturally, both in style and in matter with a self portrait that looks like John Lennon ("the superficial characteristics are the same," says Sharp) and a painting of Mick Jagger, which is also growing to look like its creator.

What you might call a van Gogh theme is becoming increasingly predominant. "The more I know of him, the more I come to feel he was a saint," Sharp says. A large portrait of Saint Vincent will be the outstanding motif of the show. Vincent appears again in the posters, with a balloon quote: "I have a terrible lucidity at moments, when nature is so glorious. In these days I am hardly conscious of myself and the picture comes to me like a dream."

Martin Sharp. scion of respectable Belleview Hill, once notorious as the author of "The Gas Lash," is a more familiar figure nowadays in the psychedelic world of the London Underground - the latter-day Bohemia - than in his native Sydney. He is back for this show, for some sunshine, and to refresh himself in the waters of beautiful Bondi. (No irony seems intended. "It" really hypnotises me," he says. "Nature in the heart of the city.'') One thinks of Sharp, Neville and Walsh as Perpetually terrible children. Martin Sharp is, in fact, a tall, slim man of 28 (almost middle aged as things go nowadays) with a heavy fall of dark hair half-hiding his face. He has made a considerable name for himself in London as a poster-designer, and has been working with Richard Neville on the London "OZ." When I was in Britain, "OZ" was, with malice aforethought, printed in type so small that no one over 30 could read it. This may soon invalidate Martin, even if be does not already feel that he and "OZ" are drifting apart. It is now, he says, revolutionary only in a large-circulation magazine sort of way. At the moment, he is experimenting in the op and pop art field, painting on clear plastic from in front and behind, in acrylic paints and enamels. It is still comment on the social scene but much less cruelly ironic than in the days when he bit the hand that fed him.

"When I lived in Sydney, I was trying to preserve my own integrity, building a wall around myself so I could exist in the middle," he says. "In London, I don't feel the necessity for this." It was a shock to come back after four years though, to find "Tharunka" being prosecuted again under the Obscene and Indecent Publications Act: pure deja vu. 1t was, after all, Sharp's prosecution and sentencing over the publication of "The Gas Lash" in Tharunka" which brought him local notoriety. Sharp's views on censorship haven't changed much: He sees the publication of the ballad "Eskimo Nell" as the action of waving a red rag at a lumbering bull, a rag which the easily stimulated bull obediently charges. Sharp has also some not-quite formulated ideas about the function of censorship in hot and cold climates. Permissiveness is allowed more easily, he thinks, in cooler climes, where the level of physical sensuality is lower, and the inhabitants are presumably less likely to be emotionally aroused. (This doesn't account for Russia or Ireland of course, but the idea is interesting.) Some o f Australia's censorship troubles, he feels, are accounted for by the dilemma of an Anglo Saxon culture being translated into a Mediterranean climate, and so becoming disoriented. Australia, excited and open, and being confronted with the cold barriers thrown up by the Customs men, was also a blow. "I had some colour slides of nudes, and they took them away and screened them," he says. "They asked if I had any pornographic literature, so I offered them a copy of 'Playboy' to placate them. It didn't work. They went through the letters of van Gogh and Patrick White's "'Tree of Man' to see if there were any dirty words in them.'' Sharp does not share the view first put forward by D. H. Lawrence, and echoed regularly ever since, that Australians are a mindless lot, obsessed solely with sensual pleasures. In the 1920s, Lawrence found no evidence that culture was alive and well and living in Sydney. "The absence of any inner meaning; and, at the same time, the great sense of a do-as-you-please liberty. And all utterly uninteresting ..... Great swarming teaming Sydney flowing out into those myriads of bungalows, like shallow water spreading undyked. And what then? Nothing. No inner life, no high command, no interest in anything, finally." But Sharp, fresh from pulsating London, finds the local scene very exciting, though he can't as yet define why. Things are happening here which are not recognised. The form is imitative, but not the content. 'That is why Australians are so successful in the London Underground," he says. "You will find that most Underground activities are run by Americans and Australians. It is the ideas which are different." Martin Sharp is the precursor of a group of expatriate Australians who will descend on us from the skies by charter plane in the coming spring. About 150 are talking of making the trip: writers, artists, film makers, rock stars, hippies, a planeload of cultural gurus, or, if you like. guerillas. It is a sort of colonial echo, Martin Sharp says. The British used to send us seminal people to stimulate our culture. Now our emissaries, carried abroad by the cultural brain drain, will return for a process of cross-fertilisation.

-------------------------------

1970-1 The Yellow House, Sydney

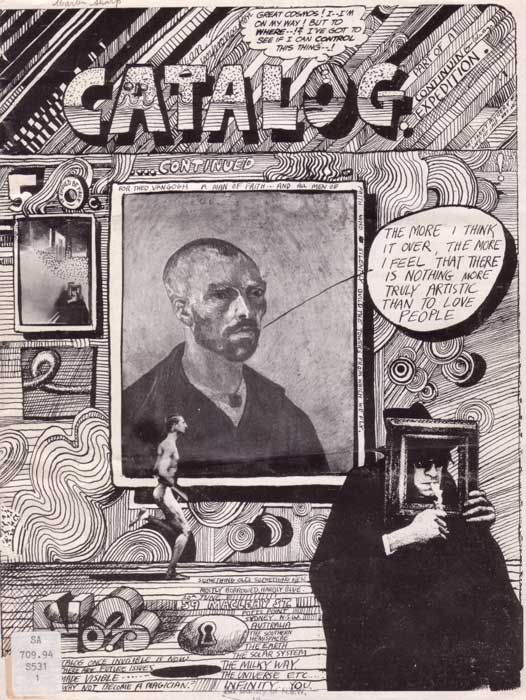

Sharp spent much of 1970 and 1971 working in Sydney and developing his own version of van Gogh's Yellow House artist community / workshop. The Dutch artist had set up a number of rooms in his residence in Arles, France, within a building painted yellow, where his artist friends such as Paul Gaughin could come and where they would work both separately and collaboratively. Unfortunately it did not work out, due in no small part to van Gogh's difficult temperament and ongoing illness. Sharp's Yellow House operated successfully through to the beginning of 1973, by which time he had returned once again to London. It is telling that the cover of his Catalog No.3 for his own exhibition at the Yellow House in 1971 heavily features van Gogh and emblazons him on the cover, almost hero-like, as a large, framed portrait, uttering the word: "The more I think it over, the more I feel that there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people." Such a statement reflects the hippie philosophy of the time - Peace and Love - and was one which Sharp and his colleagues, both in Australia and the UK, strongly believed in.

Sharp's exhibition at the old Clune Gallery in mid 1970 was entitled Public View and mainly comprised his 'artoons and paintings on mylar. Later in the year he returned briefly to London to collect his works there and return them to Australia. This resulted in The Incredible Shrinking Exhibition Part 1 which opened on April Fool's Day 1971 and was the official launch of the Yellow House, along with Catalog No.3 which he had completed the previous June. A later Yellow House newsletter from 1971 also features van Gogh and an adaptation of the Road to Tarascon, as does Catalog No.3.

Sharp produced a large number of van Gogh-related works during 1970, by which time he had returned to Sydney, ranging from the aforementioned posters and magazine illustrations, through to collage and fully developed paintings. Perhaps the most famous of these early works is the mirrored portrait, featuring two images of van Gogh's face, with a hat. This appears in a number of versions.

The more I know of him [van Gogh], the more I come to feel he was a saint. (Martin Sharp, 16 May 1970)

Sharp spent much of 1970 and 1971 working in Sydney and developing his own version of van Gogh's Yellow House artist community / workshop. The Dutch artist had set up a number of rooms in his residence in Arles, France, within a building painted yellow, where his artist friends such as Paul Gaughin could come and where they would work both separately and collaboratively. Unfortunately it did not work out, due in no small part to van Gogh's difficult temperament and ongoing illness. Sharp's Yellow House operated successfully through to the beginning of 1973, by which time he had returned once again to London. It is telling that the cover of his Catalog No.3 for his own exhibition at the Yellow House in 1971 heavily features van Gogh and emblazons him on the cover, almost hero-like, as a large, framed portrait, uttering the word: "The more I think it over, the more I feel that there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people." Such a statement reflects the hippie philosophy of the time - Peace and Love - and was one which Sharp and his colleagues, both in Australia and the UK, strongly believed in.

Martin Sharp, Catalogue No.3, June 1970. Published Sydney, 1971. Front cover.

Sharp's exhibition at the old Clune Gallery in mid 1970 was entitled Public View and mainly comprised his 'artoons and paintings on mylar. Later in the year he returned briefly to London to collect his works there and return them to Australia. This resulted in The Incredible Shrinking Exhibition Part 1 which opened on April Fool's Day 1971 and was the official launch of the Yellow House, along with Catalog No.3 which he had completed the previous June. A later Yellow House newsletter from 1971 also features van Gogh and an adaptation of the Road to Tarascon, as does Catalog No.3.

Sharp produced a large number of van Gogh-related works during 1970, by which time he had returned to Sydney, ranging from the aforementioned posters and magazine illustrations, through to collage and fully developed paintings. Perhaps the most famous of these early works is the mirrored portrait, featuring two images of van Gogh's face, with a hat. This appears in a number of versions.

|

| Martin Sharp, Mirrored Van Gogh Portrait, 1970. |

|

| Martin Sharp, Portrait of Van Gogh 1970. |

1972

Late in 1971 Sharp left Australia for London and an exhibition of his works there the following year. At the time he was heavily involved in the production of a collection of collages, and his one and only book publication - the Art Book. This thematic, fully illustrated catalogue to an exhibition features small reproductions of many of those works. They were primarily his playful juxtaposition of paintings by his favourite artists. For example, he would mix a Magritte with a van Gogh, or a Hokusai with a Goya. In April 1972 the London OZ magazine announced that Sharp was back in town with an exhibition. The announcement was within a full page colour illustration which was a psychedelic adaptation of van Gogh's The Road to Tarascon, though very much in the artist's style for the time - a simplified drawing with a travelling artist figure, a single Surreal eye, and doughnut shapes in the background, whilst the figure was walking on a ground of green and red flowers.

Martin Sharp, The Road to Tarascon, OZ magazine number 41, April 1972.

Sharp's fascination with van Gogh is reflected in the three page article published in OZ during July 1972. Focused around an 1880 letter by the artist to his brother Theo, the layout includes a full page double-headed portrait of van Gogh and another of a portrait on a chair. Both works appeared in Art Book.

Martin Sharp, OZ magazine number 43, July 1972. Page 1 of a 3 page article by Sharp.

OZ magazine number 43, July 1972. Page 1 of a 3 page article by Sharp.

OZ magazine number 43, July 1972. Page 1 of a 3 page article by Sharp.

The variants of On the road to Tarascon contained on page 3 of the OZ article include reference to Georgio de Chirico, Mickey Mouse and the American comic artist Roger Crumb. They also comprise detailed pen and ink drawings in black and white with colour added as part of the publication process.

1973

Sharp returned to Australia in January 1973 and began a process of working with Tim Lewis to reproduce in paint and on a larger scale some of his 'artoons for an exhibition in March at the Bonython Art Gallery, Sydney. Entitled The Art Exhibition - A Yellow House Production with Tim Lewis, it also marked the official Australian launch of Art Book. This year was another busy one for Sharp and his van Gogh fascination, with completion of works such as Still Life 1973, Vincent's Chair 1973 and another version of The Road to Tarascon, this time titled Icarus 1973 and with only a shadow to show where the artist once was.

Martin Sharp, Icarus, 1973.

A Sharp 'artoon appeared in the final edition of London OZ, November 1973. Comprising a cartoon Superman with a Van Gogh Starry Night background alongside an anonymous Death Poem, the colourful two-page spread was perhaps the most dynamic part of the magazine.

Martin Sharp, Superman Starry Night, OZ magazine, London, November 1973.

------------------------

1977 and beyond

In 1977 Sydney artist and critic Elwyn Lynn wrote an article in Quadrant magazine on Martin Sharp's skill with collage. Entitled Those Silver Scissors, the piece featured a number of his van Gogh related works and 'artoons from the late 60s and early 70s. During 1979 the Art Gallery of New South Wales travelling exhibition entitled Art in the Making focused on the processes involved in producing art. Martin Sharp was one of the featured artists, and the accompanying catalogue included reproductions of a number of his 'artoons and van Gogh related works, along with comments by the artist on his relationship with the Dutch painter. In addition to reworking paintings by van Gogh and combining them with the work of others, Sharp also on occasion dropped a van Gogh object or motif into a foreign painting. For example, one of the 'artoons published in Art Book was a combination of an indoor scene from Henri Matisse Large Red Interior 1948 and the dove of Rene Magritte's The Great Family 1963.

In 1986 Sharp adapted the 'artoon by producing a painting which replaced the Matisse chair with van Gogh's chair and pipe as the centerpiece. The dove was also brought into the room and the work titled Pentecost.

In 1977 Sydney artist and critic Elwyn Lynn wrote an article in Quadrant magazine on Martin Sharp's skill with collage. Entitled Those Silver Scissors, the piece featured a number of his van Gogh related works and 'artoons from the late 60s and early 70s. During 1979 the Art Gallery of New South Wales travelling exhibition entitled Art in the Making focused on the processes involved in producing art. Martin Sharp was one of the featured artists, and the accompanying catalogue included reproductions of a number of his 'artoons and van Gogh related works, along with comments by the artist on his relationship with the Dutch painter. In addition to reworking paintings by van Gogh and combining them with the work of others, Sharp also on occasion dropped a van Gogh object or motif into a foreign painting. For example, one of the 'artoons published in Art Book was a combination of an indoor scene from Henri Matisse Large Red Interior 1948 and the dove of Rene Magritte's The Great Family 1963.

Martin Sharp, Henri Matisse Large Red Interior 1948 / Rene Magritte's The Great Family 1963.

In 1986 Sharp adapted the 'artoon by producing a painting which replaced the Matisse chair with van Gogh's chair and pipe as the centerpiece. The dove was also brought into the room and the work titled Pentecost.

|

| Martin Sharp, Pentecost, 1986. |

A later version from 2006 completely removes the window and masks the whole view in red drops like rain. A rising sun on the horizon is also included, along with a map of Australia.

|

Martin Sharp, Pentecost, May 2006.

|

Sharp's 2007 version of The Road to Tarascon combines van Gogh's

original composition with the look of a Japanese woodblock print - refer

the silhouette of Mount Fuji in the background - and Sharp's own

distinctive use of large, thick applications of bright colour, perhaps a

carryover from his psychedelic experiences in London during the late

Sixties.

The yellow tone of the original work by Van Gogh is replaced with a red / orange combination, and the yellow, whilst still present, assumes a lesser role. Another work from the early 1970s in a European private collections features a collection of motifs and colours, with a self portrait in the centre, a painted background, an all encompassing thin orange circle and red and blue and bark brown flames fanning out to the edge of the work. It is spectacular.

Martin Sharp, The Road to Tarascon, 2007.

The yellow tone of the original work by Van Gogh is replaced with a red / orange combination, and the yellow, whilst still present, assumes a lesser role. Another work from the early 1970s in a European private collections features a collection of motifs and colours, with a self portrait in the centre, a painted background, an all encompassing thin orange circle and red and blue and bark brown flames fanning out to the edge of the work. It is spectacular.

------------------------

Appendix 1

* Margaret Jones, Whatever happened to Martin Sharp?, Sydney Morning Herald, 16 May 1970.

* Margaret Jones, Whatever happened to Martin Sharp?, Sydney Morning Herald, 16 May 1970.

Whatever happened to Martin Sharp?

Margaret Jones discovers that the terrible triplet of 'OZ' days has turned to simple images.

"The images have been imprisoned inside me for too long: they want to get out," says Martin Sharp, clattering through the old Clune galleries in Macleay Street, in heavy-blue clogs, long bob swinging on denimed shoulders. The images appear in lithographs stacked against the walls, in silk screen on plastic, in works.in-progress stretched out on the floor for want of other space. Sharp is not yet ready for the opening of his show of paintings, collages, lithographs and posters next Wednesday. "Life is a whirlpool draining towards a small hole," he says, with an air of gentle perturbation. Whatever happened to the old Martin Sharp, with his savage comic-strip fables, his elaborate collages, his inspiring attacks on Establishment figures, who often immortalised their own inanities in the balloons issuing forth from their mouths? Whatever happened to the terrible triplet, who, with Richard Neville and Richard Walsh, published the highly satirical magazine "Oz"? The old Sharp still exists, manifesting in the posters and collages, particularly some of the vintage works. The posters are a special joy, richly ornamental as well as significant, ravishing in gold and silver. But, on the whole, these days the images are simple, profound, and quintessential: hearts, flying objects, flowers with human lips for blossoms, an unadorned question mark. Space gets a passing glance, as in a portrait of an astronaut against a galactic background. Pop is present, naturally, both in style and in matter with a self portrait that looks like John Lennon ("the superficial characteristics are the same," says Sharp) and a painting of Mick Jagger, which is also growing to look like its creator.

What you might call a van Gogh theme is becoming increasingly predominant. "The more I know of him, the more I come to feel he was a saint," Sharp says. A large portrait of Saint Vincent will be the outstanding motif of the show. Vincent appears again in the posters, with a balloon quote: "I have a terrible lucidity at moments, when nature is so glorious. In these days I am hardly conscious of myself and the picture comes to me like a dream."

Martin Sharp. scion of respectable Belleview Hill, once notorious as the author of "The Gas Lash," is a more familiar figure nowadays in the psychedelic world of the London Underground - the latter-day Bohemia - than in his native Sydney. He is back for this show, for some sunshine, and to refresh himself in the waters of beautiful Bondi. (No irony seems intended. "It" really hypnotises me," he says. "Nature in the heart of the city.'') One thinks of Sharp, Neville and Walsh as Perpetually terrible children. Martin Sharp is, in fact, a tall, slim man of 28 (almost middle aged as things go nowadays) with a heavy fall of dark hair half-hiding his face. He has made a considerable name for himself in London as a poster-designer, and has been working with Richard Neville on the London "OZ." When I was in Britain, "OZ" was, with malice aforethought, printed in type so small that no one over 30 could read it. This may soon invalidate Martin, even if be does not already feel that he and "OZ" are drifting apart. It is now, he says, revolutionary only in a large-circulation magazine sort of way. At the moment, he is experimenting in the op and pop art field, painting on clear plastic from in front and behind, in acrylic paints and enamels. It is still comment on the social scene but much less cruelly ironic than in the days when he bit the hand that fed him.

"When I lived in Sydney, I was trying to preserve my own integrity, building a wall around myself so I could exist in the middle," he says. "In London, I don't feel the necessity for this." It was a shock to come back after four years though, to find "Tharunka" being prosecuted again under the Obscene and Indecent Publications Act: pure deja vu. 1t was, after all, Sharp's prosecution and sentencing over the publication of "The Gas Lash" in Tharunka" which brought him local notoriety. Sharp's views on censorship haven't changed much: He sees the publication of the ballad "Eskimo Nell" as the action of waving a red rag at a lumbering bull, a rag which the easily stimulated bull obediently charges. Sharp has also some not-quite formulated ideas about the function of censorship in hot and cold climates. Permissiveness is allowed more easily, he thinks, in cooler climes, where the level of physical sensuality is lower, and the inhabitants are presumably less likely to be emotionally aroused. (This doesn't account for Russia or Ireland of course, but the idea is interesting.) Some o f Australia's censorship troubles, he feels, are accounted for by the dilemma of an Anglo Saxon culture being translated into a Mediterranean climate, and so becoming disoriented. Australia, excited and open, and being confronted with the cold barriers thrown up by the Customs men, was also a blow. "I had some colour slides of nudes, and they took them away and screened them," he says. "They asked if I had any pornographic literature, so I offered them a copy of 'Playboy' to placate them. It didn't work. They went through the letters of van Gogh and Patrick White's "'Tree of Man' to see if there were any dirty words in them.'' Sharp does not share the view first put forward by D. H. Lawrence, and echoed regularly ever since, that Australians are a mindless lot, obsessed solely with sensual pleasures. In the 1920s, Lawrence found no evidence that culture was alive and well and living in Sydney. "The absence of any inner meaning; and, at the same time, the great sense of a do-as-you-please liberty. And all utterly uninteresting ..... Great swarming teaming Sydney flowing out into those myriads of bungalows, like shallow water spreading undyked. And what then? Nothing. No inner life, no high command, no interest in anything, finally." But Sharp, fresh from pulsating London, finds the local scene very exciting, though he can't as yet define why. Things are happening here which are not recognised. The form is imitative, but not the content. 'That is why Australians are so successful in the London Underground," he says. "You will find that most Underground activities are run by Americans and Australians. It is the ideas which are different." Martin Sharp is the precursor of a group of expatriate Australians who will descend on us from the skies by charter plane in the coming spring. About 150 are talking of making the trip: writers, artists, film makers, rock stars, hippies, a planeload of cultural gurus, or, if you like. guerillas. It is a sort of colonial echo, Martin Sharp says. The British used to send us seminal people to stimulate our culture. Now our emissaries, carried abroad by the cultural brain drain, will return for a process of cross-fertilisation.

-------------------------------

References

Brett Whiteley and Martin Sharp - Homage to Van Gogh, Shapiro Auctions, Sydney, December 2014. URL: http://shapiro.com.au/News/brett-and-sharp-homage-to-van-gogh/.

James, Rodney, after Van Gogh: Australian artists in homage to Vincent, An MRPG Exhibition, Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery, 6 September - 30 October 2006, 44p.

Lindsay, Robert, Martin Sharp, Survey14 [exhibition catalogue], National Gallery of Victoria, 15 May - 4 July 1981, 8p.

Lynn, Elwyn, Those Silver Scissors, Quadrant, February 1977, 45-47.

Sharp, Martin, Art Book, London, 1972.

Slutzkin, Linda and Haynes, Peter, Art in the Making, Travelling Exhibition, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1979-80.

The 10 most wanted missing artworks from World War II, The South African Art Times - International [blog], 8 November 2013. URL: http://arttimes.co.za/top-10-wanted-missing-art-works-world-war-ii/.

Underground Graphics, Academy Editions, London, 1970.

James, Rodney, after Van Gogh: Australian artists in homage to Vincent, An MRPG Exhibition, Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery, 6 September - 30 October 2006, 44p.

Lindsay, Robert, Martin Sharp, Survey14 [exhibition catalogue], National Gallery of Victoria, 15 May - 4 July 1981, 8p.

Lynn, Elwyn, Those Silver Scissors, Quadrant, February 1977, 45-47.

Sharp, Martin, Art Book, London, 1972.

Slutzkin, Linda and Haynes, Peter, Art in the Making, Travelling Exhibition, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1979-80.

The 10 most wanted missing artworks from World War II, The South African Art Times - International [blog], 8 November 2013. URL: http://arttimes.co.za/top-10-wanted-missing-art-works-world-war-ii/.

Underground Graphics, Academy Editions, London, 1970.

-----------------------

Michael Organ, Australia

Last updated: 21 March 2018

Absolutely brilliant insight into the life and works of Martin Sharp!

ReplyDeleteSuperb words and reprints!

Thank you Michael :-)